Displacement, Gentrification, and Maryland’s Purple Line Light Rail

In Maryland’s suburban counties of Montgomery and Prince George’s, the state government and a public-private partnership are spending billions of dollars to construct a new light rail rapid transit line. Who will benefit from this multi-billion dollar investment in the Purple Line light rail system? Will existing residents be displaced by upscale development and high income households? Or can the areas adjacent to the new transit line become a national model for racial and income integration as a part of new transit-oriented development?

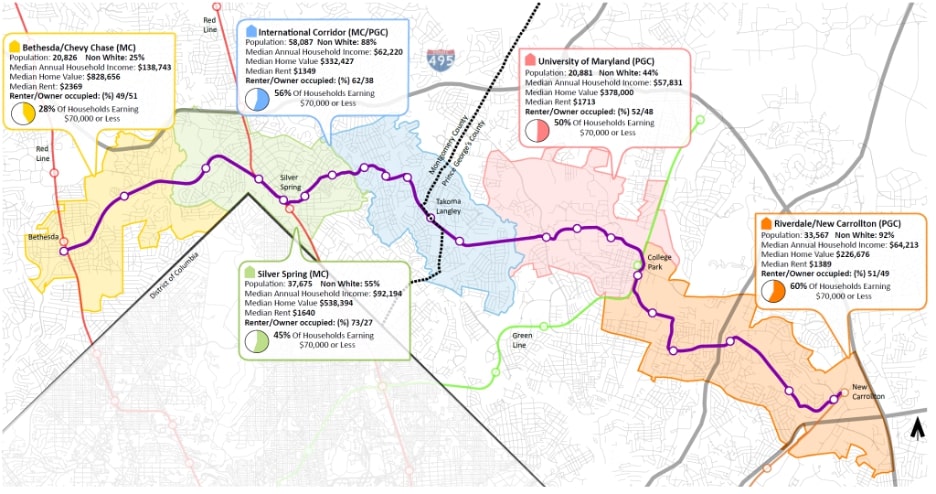

The Purple Line, the DC metropolitan region’s first circumferential rail transit, will open by 2027 (Map 1). This light rail line will connect existing Metrorail lines at multiple densely populated activity and employment centers and provide fast and sustainable public transportation across the suburbs. It will connect some of the region’s wealthiest areas, like Bethesda and Chevy Chase, to some of its most disadvantaged, like Riverdale and Langley Park. Disadvantaged communities have always been distant from Metrorail transit and have historically received less public and private infrastructure investment, creating a reinforcing cycle of disinvestment and concentrated poverty.

In less than five years, these areas will be home to multiple new light rail stations, complete with public art, pedestrian and bicycle access improvements, and changes to local streets. These areas are also home to majority Black and Latinx populations, and in the DC region as elsewhere, these populations are subject to significant social and economic disadvantage. While these areas and populations desperately need better access to public transit, safer streets, and more commercial and public amenities, residents and other stakeholders are wary. Many believe that the investment in the Purple Line could bring rapid social and economic change, and that they may therefore be excluded from continuing to live in these communities (Shaver, 2022).

Figure 1. The Purple Line Corridor and its subareas, with Demographic Context

Source: NCSG analysis of US Census ACS Data

Significant investments in public transportation can potentially catalyze gentrification (Zuk et al. 2018). Gentrification is the process by which new residents with higher incomes move into formerly disinvested areas, which can lead to displacement of incumbent residents and their businesses, culture, and social networks (Finio, 2021). Displacement refers to the forced exit, or blocked relocation into, of lower income residents or business owners in gentrifying areas. In and around Washington DC, gentrification has been found to be linked with displacement of primarily Black populations from urban, central city neighborhoods; with a significant social cost including loss of culture and social cohesion (Hyra, 2017; Jackson, 2015). Anyone who is familiar with the Washington DC region knows just how different neighborhoods including Petworth, Columbia Heights, Shaw and even Anacostia are today than they were in the 1980s, 1990s, or even 2000s.

Gentrification, and its primary consequence of displacement, are highly complex and contested processes. Overall, research indicates that displacement can have financial and psychological consequences for lower income households, and can force them to move further away from where they’d like to live (Pattillo 2007; Betancur, 2011). However, the extent of displacement remains unclear (Freeman, 2005; Delmelle and Nilsson 2020).

A preliminary analysis

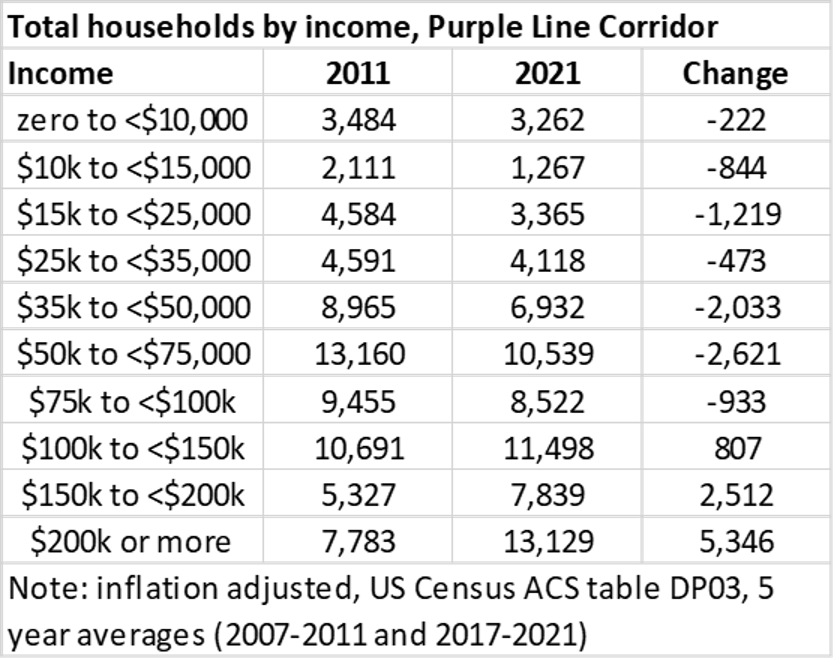

Changes to the income distribution of households in the Purple Line Corridor suggest that some of these deleterious changes are already occurring. Census data can describe how the composition of a region’s population has changed, though it does not enable tracking of specific households. The table below contains data on median household incomes for households living in the Purple Line Corridor (the shaded areas in Map 1).

It shows that from 2011 to 2021, there were significant changes in the income distribution of the Purple Line Corridor’s households (Table 1). These changes pushed the corridor towards having more income inequality, as there was a large increase in the number of high-income households and a decrease in low-income households. The number of households with incomes under $100,000 fell in all brackets; and rose for all brackets above $100,000, even after adjusting for inflation. Fewer low-income households call the Corridor home today than did 10 years prior, even in advance of the Purple Line’s opening.https://coascenters.howard.edu/media/1971

Table 1. Households by Income, Purple Line Corridor

Source: NCSG Analysis of US Census ACS data

Note: Inflation adjusted to 2021 dollars using CPI-U-RS

This simple accounting evidence from the census shows that the area in which new transit is being built is already potentially experiencing one potential consequence of gentrification: displacement. One central and mostly disadvantaged neighborhood – Long Branch – has yet to see extensive development but is already feeling upward pressure on real estate prices. In this area, like many others, rents have been rising in real terms for years, beating the rate of inflation, and costing renters hundreds more per month (Purple Line Corridor Coalition, 2019).

These early results indicate that a lack of affordable housing options could be driving lower income people out of the corridor. If the corridor is indeed gentrifying, higher income households are bidding up rents and home prices, making it tough for lower income households to compete. Potential policy solutions include increasing the supply of subsidized affordable housing, protecting existing affordable housing in perpetuity, and also construction of more housing, period. The Purple Line Corridor Coalition and the National Center for Smart Growth recently completed a two-year long, stakeholder input driven research process to plan for more equitable transit-oriented development in the Corridor. You can learn more about that work, funded by the Federal Transit Administration, here. Work on this topic continues, and future blogs will provide more data and analysis concerning the burning question of whether the Purple Line Corridor is experiencing gentrification and displacement.

About the Author: Nick Finio is a CHURP Research Fellow, and works for the National Center for Smart Growth (NCSG) at the University of Maryland, College Park. At UMD, he is an Assistant Research Professor and the Associate Director of NCSG, where he supports the activities of the Purple Line Corridor Coalition. I may be reached at nfinio@umd.edu.

Sources:

Betancur, John. 2011. “Gentrification and Community Fabric in Chicago.” Urban Studies 48 (2): 383–406. https://doi.org/10.1177/0042098009360680.

Delmelle, Elizabeth, and Isabelle Nilsson. 2020. “New Rail Transit Stations and the Out-Migration of Low-Income Residents.” Urban Studies 57 (1): 134–51. https://doi.org/10.1177/ 0042098019836631.

Finio, Nicholas. 2021. “Measurement and Definition of Gentrification in Urban Studies and Planning.” Journal of Planning Literature 37 (2): https://doi.org/10.1177/08854122211051603.

Freeman, Lance. 2005. “Displacement or Succession? Residential Mobility in Gentrifying Neighborhoods.” Urban Affairs Review 40 (4): 463–91. https://doi.org/10.1177/1078087404273341.

Hyra, Derek. 2017. Race, Class and Politics in the Cappuccino City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jackson, Jonathan. 2015. “The Consequences of Gentrification for Racial Change in Washington, DC.” Housing Policy Debate 25 (2): 353–73. doi: 10.1080/10511482.2014.921221.

Pattillo, Mary. 2007. Black on the Block: The Politics of Race and Class in the City. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Purple Line Corridor Coalition. 2019. Purple Line Corridor Coalition Housing Action Plan. Purple Line Corridor Coalition, National Center for Smart Growth, College Park MD. https://purplelinecorridor.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/12/HAP-Full-Report-06-Dec-2019.pdf

Shaver, 2022. September 30th. “As Purple Line construction resumes, the fight against gentrification is on.” The Washington Post. Washington, DC. https://www.washingtonpost.com/transportation/2022/09/30/purple-line-maryland-gentrification/

Zuk, Miriam, Ariel H. Bierbaum, Karen Chapple, Karolina Gorska, and Anastasia Loukaitou- Sideris. 2018. “Gentrification, Displacement, and the Role of Public Investment.” Journal of Planning Literature 33 (1): 31–44. doi: 10.1177/0885412217716439.