Encampment Living in New York City: Police Sweeps or Housing First?

Jasmine Fuller, CHURP Research Fellow

Manish Adhikari, CHURP Student Research Fellow

Prasun Dhungana, CHURP Student Research Fellow

Ajeune Lynch, CHURP Student Research Fellow

Homelessness in U.S. cities is rapidly growing and sparking city-led interventions to clear encampments. Yet there is inadequate shelter space for people experiencing homelessness and many reject shelter regimentation and fear danger that they perceive in such spaces. Clearing encampments is both futile and inhumane. What can be done?

Urban Homelessness in the U.S.

Rising rents, affordable housing shortages, stagnant wages, and other social factors drive homelessness in the U.S. The number of households paying more than 50% of their income on rent increased by 12% over the past decade (National Alliance to End Homelessness (NAEH), 2024). In the same period homelessness grew over 36%; in 2024 the number of people experiencing homelessness (PEH)[1] reached 771,480 (Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD), 2024). Homelessness is both a public health and humanitarian crisis. The experience of homelessness has well-documented long-term consequences for individual health and well-being. Between 17,500 and 46,000 people experiencing homelessness died in 2018 due to the dangerous conditions caused by living without housing (National Health Care for the Homeless Council, 2021).

[1]People experiencing homelessness (PEH) are individuals without stable, safe, permanent, appropriate housing, or the immediate prospect, means and ability of acquiring it. PEH may be living on the streets, in encampments or shelters, in transitional housing programs, or doubled up with family and friends.

While the number of temporary and permanent shelter beds increases annually, such growth is unable to keep up with the rising number of people experiencing homelessness. More than 50% of PEH today are unsheltered and use encampments as an alternative to shelters (NAEH, 2024). Urban localities have responded forcefully by clearing these encampments following a Supreme Court ruling allowing cities to ban “camping”, or sleeping outside, supposedly because of health and safety concerns. Local governments in New York, Los Angeles and other cities have launched street encampment clearing task forces that dismantle encampments of PEH and discard their belongings. Critics have called these actions costly, inhumane and ineffective.

Homelessness in New York City

Growing migrant populations, increasing rents, gentrification, and a limited housing stock has doubled homelessness in New York City (NYC) in the last decade. In the city of New York alone more than 103,200 people were experiencing homelessness in 2023, accounting for 16% of the national unhoused population. New York PEH often rely on encampments for shelter. Encampments – “structures to live under” include makeshift living arrangements including mattresses, tents, tarps and other forms of outdoor living setups (HUD, 2021). These structures are often set up in public areas like subways and under bridges.

Many PEH prefer encampment living because it offers them privacy, stability, a sense of community within the encampment, and autonomy, such as setting their own schedule instead of shelter curfews, or deciding to own a pet. Limitations in the shelter system also contribute to popularity of encampments (Cohen et al., 2019). The availability of shelter beds is limited and inconsistent in New York. Furthermore, shelter opening and closing times are often inconvenient and admission requirements may exclude, families, women, or young children. Sexual assault and violence in shelters has been reported to be rampant (Kerman, 2023). 19% of adults experiencing homelessness have reported being physically or sexually abused while homeless, and 22 % of PEH who identify as transgender reported being sexually assaulted, by residents or staff while staying in a homeless shelter (Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault, 2017). As homelessness increases, without increases in affordable housing or other temporary or permanent housing services, encampment living will increase with or without sweeps.

Figure 1: The tents of “Anarchy Row” on the Lower East Side as they stood on March 30, 2022, before encampment clearing task force sweeps. Source: Luke Cregan for NY City Lens.

Encampment Challenges in NYC

Encampments are a common sight in many urban settings including NYC. While they may serve as temporary shelters for people experiencing homelessness, outdoor living can pose significant risks to both their occupants and possibly the larger community. Homeless encampments are often crowded, lack running water or proper waste disposal systems, which can be a cause for concern.

To address the risks specific to encampments, NYC’s government began clearing or sweeping encampments found in the city. The encampment clearing task force established by Mayor Adams combined personnel from the Department of Homeless Services (DHS), the New York Police Department (NYPD), the Department of Sanitation (DoS), and the Department of Recreation. A typical sweep in NYC begins, in theory, with a visit from the police department to determine if the encampment is eligible for clean-up, after which a representative from the DHS offers PEH living in the encampment social services including temporary housing or medical treatment. Then a notice is issued to encampment residents 24 hours in advance of any sweeping efforts so they can clear their belongings.

From April to June 2024, total spending on encampment activities reached up to $ 1 million dollars, $300,000 of which was spent on the presence of NYPD officers at removal sites (NYC DHS, 2024). The excessive costs of sweeps redirect already limited funding and resources away from shelters and permanent housing. Encampment sites are homes for many individuals and displacing them along with their belongings violates several human rights and puts them at risk. Sweeps often forcibly relocate individuals away from essential services which may lead to substantial increases in overdose deaths, hospitalizations, and life-threatening infections and hinder access to medications for opioid use disorder (and other detrimental impacts). Encampment sweeps, bans and move-along orders could contribute to 15-25% of deaths among the unsheltered population over 10 years (Journal of the American Medical Association, 2024). The NYC task force is instructed to provide at least 48 hours’ notice ahead of sweeps and store people’s collected belongings for up to 90 days. However, the Urban Justice Center believes these procedures are regularly violated (Hogan, 2024). A lawsuit filed by six homeless individuals in NYC states that the city is violating 4th Amendment protections against unreasonable searches and seizures. Similar litigation is happening in other cities such as Los Angeles, California.

Does “sweeping” reduce the number of PEH living in encampments?

In 2022, New York City Mayor Adams inaugurated an encampment clearing task force, but the program neither effectively eliminated encampments nor connected PEH with housing services. A recent audit of 99 encampment sites in NYC found that PEH had returned to nearly a third of the cleared sites and by 2023 only three PEH secured permanent housing. We performed our own analysis to investigate the effectiveness of the task force in clearing the presence of encampments in NYC. We share our findings below.

New York City conducted an average of 500 encampment clearings every month through the fall of 2024. City officials report that their task force has gone out more than 11,500 times and cleared 6,800 locations since March 2022. By comparing locations of cleared encampments with reports of encampment sightings from residents, we were able to assess the effectiveness of the sweeps in achieving their stated goal -- eliminating encampment living in NYC.

Using data from the NYC DoS, we examined locations of encampment sweeps that occurred in the city between 2022 and 2024. Then, using 311 data we examined the locations of PEH encampments in NYC. (New Yorkers can call 311 to report sightings of homeless encampments). For each call, location and time details are recorded, which can be used to determine the location of encampments in NYC 2. Neighborhood level data offered by 311 calls can effectively capture the differing care options, habits, and hazards faced by those experiencing homelessness in NYC. This includes location of shelters and homeless service centers, as well as community-reported crime, air pollution and extreme heat risks.

2There are other datasets that describe unhoused populations, like HUD’s Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR). However, AHAR does not specify locations of unhoused populations below the county level of aggregation.

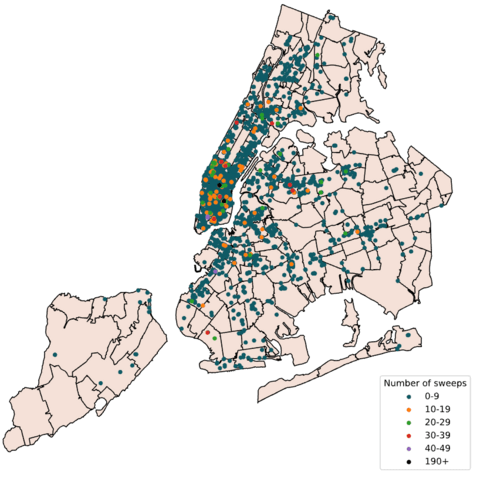

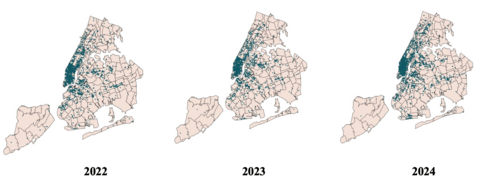

Locations of encampment sweeps between 2022-2024 are shown in Figure 2. Most encampment clearings occurred in the northwestern part of NYC (Manhattan and Brooklyn). Clearings were less frequent in southern and eastern parts of the city where Staten Island and Queens are located. Sweep location trends mimic trends in the presence of homelessness in NYC. Annual locations of 311 encampment sightings are shown in Figures 3-6. Throughout 2022-2024, there is a large cluster of homeless-related calls in northwestern NYC including Manhattan. Calls are scarcer in southern and eastern parts of the city in Queens and Staten Island. Mid-town Manhattan is where most sweeps occurred, and where over 22% of the city’s PEH are sighted. In Staten Island, the least number of sweeps occurred, and less than 0.3% of the city’s PEH were sighted there. Over time these trends remain unchanged even though almost 8,000 individual sweeps occurred in NYC to reduce the presence of PEH. Although encampment sweeps are accurately targeting places where encampments are present, encampment locations have remained unchanged since sweeping began in 2022. The 311-call map from 2021 is not substantially different from the 311-call map from 2024, which suggests that, following the sweeps, PEH returned to their original or nearby locations to reestablish their encampments.

Figure 2: Locations of NY City Department of Sanitation Encampment Sweeps (2022-2024)

Figure 3: Map of Homelessness-related 311 Calls in NYC (2022, 2023, & 2024)

STOP Encampment Clearing Task Forces

There is considerable evidence that encampment sweeping is ineffective at reducing encampment living in NYC. Our analysis reveals encampment clearings completed in NYC from 2022-2024 were not effective at reducing encampment living or homelessness in NYC. While encampment sweeps did accurately target places where encampments were present, PEH returned to their original or nearby locations to reestablish their encampments following the sweeps.

The NYC government’s sweeping task force was nominally tasked to carry out an “enhanced effort to connect New Yorkers experiencing homelessness with social services.” However, only 5% of PEH engaged during clearing procedures accepted temporary shelter and even a lower share stayed in the shelter for any length of time. Instead, sweeps often forcibly relocate PEH away from essential services. The low success rate in moving people from the street to shelter and housing suggests that sweeping is not an effective method to connect PEH to housing or services just as it has failed to permanently clear encampments.

Rehousing goals for the number of PEH in NYC are unrealistic. The population of PEH is growing at a faster rate than the creation of affordable housing in NYC. In 2021, the shortage of affordable housing reached a point of crisis, with almost every income group across the five boroughs experiencing negative effects of high rent burden. The current unavailability of affordable housing exacerbates homelessness in NYC and causes barriers to housing existing PEH.

Recent government efforts like camping bans and encampment sweeping have not addressed homelessness in NYC and have instead made life for PEH more dangerous. Sweeping and similar efforts should end in NYC and other cities. Spending should be retargeted toward developing affordable housing and other services to house PEH and other income-constrained New Yorkers. Housing First is a homeless assistance approach that prioritizes providing permanent housing to people experiencing homelessness. It does not require people experiencing homelessness to address all of their problems including behavioral health problems or to graduate through a series of services programs before they can access housing. There is a large and growing evidence base demonstrating that Housing First is an effective approach to reducing homelessness. Consumers in Housing First models access housing faster and are more likely to remain stably housed. A variety of studies have shown that between 75 percent and 91 percent of households remain housed a year after being rapidly re-housed (National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022; Peng et al. 2021). If we as a society wish to seriously reduce the harm experienced by PEH and the broader negative social impacts associated with homelessness, it is high time that local, state, and federal policy makers drop the repressive inhumane practices of sweeping encampments and rapidly build housing units for this population.

References

- Barocas J., Nall S., Axelrath S., et al. Population-level health effects of involuntary displacement of people experiencing unsheltered homelessness who inject drugs in U.S. cities. JAMA. 2023;329(17):1478–1486.

- Cohen, R.; Yetvin, W. & Khadduri, J. "Understanding Encampments of People Experiencing Homelessness and Community Responses: Emerging evidence as of late 2018." The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2019, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Understanding-Encampments.pdf, Accessed April 2025.

- de Sousa, T. & Henry, M. "The 2024 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR) to Congress." The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, Abt Global, 2024, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/2024-AHAR-Part-1.pdf, Accessed April 2025.

- Hogan, G. “NYC’s homeless camp sweeps violate constitution, lawsuit claims”, The City, Oct. 2024, https://www.thecity.nyc/2024/10/30/homeless-encampment-sweeps-unconstitution-lawsuit/, Accessed April 2025.

- Kerman, N., et al. "Victimization, safety, and overdose in homeless shelters: A systematic review and narrative synthesis." Health & Place 83 (2023): 103092.

- “Local Law 34 of 2024 Quarterly Interagency Reporting on Encampment Cleanups and Aided Removals”, New York City Department of Homeless Services, 2024, https://www.nyc.gov/site/dhs/about/stats-and-reports.page, Accessed April 2025

- “National Homeless Mortality Overview.” National Healthcare for the Homeless Council, Dec. 2020, https://nhchc.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/12/Section-1-Toolkit.pdf, Accessed April 2025.

- Peng, Yinan, et al. "Permanent supportive housing with housing first to reduce homelessness and promote health among homeless populations with disability: a community guide systematic review." Journal of Public Health Management and Practice 26.5 (2020): 404-411.

- Short, M. “Sexual violence against people experiencing homelessness and marginal housing”. Maryland Coalition Against Sexual Assault, 2017, https://mcasa.org/newsletters/article/homeless-survivors-article#:~:text=A%20study%20of%20people%20experiencing,the%20previous%20year%20%5B2%5D, Accessed April 2025.

- Soucy, D.; Janes, M. & Hall, A. "State of Homelessness: 2024 Edition." National Alliance to End Homelessness, 5 Aug. 2024, https://endhomelessness.org/state-of-homelessness, Accessed April 2025.

- “The evidence is clear: Housing first works” National Low Income Housing Coalition, 2022, https://nlihc.org/sites/default/files/Housing-First-Evidence.pdf, Accessed April 2025.

- “Unsheltered Homelessness and Homeless Encampments in 2019.” The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development, 2021, https://www.huduser.gov/portal/sites/default/files/pdf/Unsheltered-Homelessness-and-Homeless-Encampments.pdf, Accessed April 2025.