Today’s Gentrification: Policy Regimes Hindered Wealth Generation from Black Homeownership in the District of Columbia

Angela J. Bodley, CHURP Research Fellow

Gentrification is not a naturally occurring economic process. Its roots are in significant, conscious, and calculated actions generated by anti-Black policies and practices undertaken by governments, individuals, and corporations. Decades of anti-Black discriminatory practices and strategic disinvestment and reinvestment in the District of Columbia have ultimately uprooted thousands of families while establishing new exclusionary communities.

In the last two decades, Washington D.C. has changed from a majority Black and vibrantly-cultured “Chocolate City” to upscale restaurants and cafes catering to a new breed of mainly non-Black newcomers, and an area where many long-term Black residents are unable to flourish. A hub of Black homeownership, community, and culture became dominated by a White upper-middle class population largely unaware of the culture and people they were displacing.

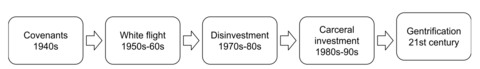

Figure 1. White Reclamation Trajectory from Golash-Boza 2023, p.158.

Tanya Golash-Boza’s 2023 book Before Gentrification reveals the sinister steps leading to the displacement of D.C.’s Black residents: redlining, White flight, disinvestment, and carceral investment, followed by reinvestment for newcomers and Black displacement. Drawn from interviews with victims of D.C.’s war on drugs, Golash-Boza recounts the challenges families faced including barriers to homeownership and the wealth it could generate, the District’s school-to-prison pipeline, and the daunting challenge of returning to a gentrified city (page numbers cited alone refer to this book).1

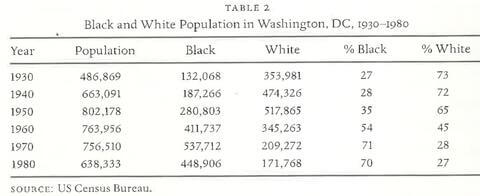

Washington D.C. was a segregated capital city after the Civil War. By 1930, it was 27% Black and 73% White. The demographics of Washington D.C. did not start drastically changing again until the 1950s, when Black people would soon reach the majority (p. 52).

Figure 2. (p. 52)

Black homeownership obstacles

In 1948 the U.S. Supreme Court ruled that racially restrictive covenants on homes in D.C. neighborhoods were not to be legally enforced (p. 157), so Black people technically had the legal right to purchase homes but also faced massive resistance. Following mandated school desegregation from the 1954 Brown vs. Board of Education case, many White residents fled to the suburbs as previously White-only schools began accepting Black students. As White families acted on their internalized racist myths about Black people, they often lost financially in their rush to depart. Ironically, more real estate became available in previously all-White neighborhoods with better schools and better public amenities that Black families could now occupy (p. 6).

Brown vs. Board of Education had outlawed segregation in schools, but the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed discrimination in essentially all spaces. It was followed by the Civil Rights Act of 1968, also known as the Fair Housing Act, by President Lyndon Johnson. This expanded policy focused on discrimination in housing, but de jure pronouncements did not end the assault on Black individuals aspiring to build wealth through homeownership.

Prior to the 1950s, the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation (HOLC) of 1933 and the New Deal Fair Housing Act of 1940 worked to limit Black homeownership (p. 42). HOLC lowered interest rates and increased the payback period only in neighborhoods where HOLC and the Federal Housing Administration (FHA) estimated the value likely to be stable or increase and meet minimum building standards. These neighborhoods tended to be exclusively White. The FHA and HOLC grading of neighborhoods was heavily influenced by neighborhood demographics. HOLC and FHA limited private housing for Black families to “save the city”.

After desegregation, previously White neighborhoods, such as Petworth, became home to many Black middle-class families. Neighborhoods including Navy Yard, which had begun accepting Black residents after the Civil War, soon became all Black. After the Fair Housing Act of 1968 reinforced the prohibition of discrimination in housing in the Civil Rights Act, Black people were able to officially buy homes in White neighborhoods, which soon became majority Black. From 1940 to 1980 Black homeownership increased by 700% in Washington, D.C., with the bulk of the change occurring with the legislative initiatives of the 1960s (p. 19).

As more Black people moved to Washington D.C., more White people fled. With the help of anti-Black racism in policies, fear tactics, and the appeal of the suburbs, half of D.C.’s White residents left between 1950 and 1970. The FHA and real estate agents warned White homeowners of the damages that living in proximity to Black people would do to their property values. However, many White families already had anti-Black sentiment around their children sharing an education with Black children. Reinforcing such prejudice, the government offered subsidized loans and 30-year mortgages with lower interest rates to White families escaping to the suburbs (p. 52). There were five times the number of subsidized mortgages in the new suburb of Montgomery County, Maryland. Real estate agents were able to profit from White flight by selling homes to the influx of Black people moving into previously White-only neighborhoods.

Figure 3. FHA grading map of D.C. in 1937 from National Archives.2

During the boom in Washington D.C.’s Black population, the government continued grading districts with letters A through H, with the latter letter indicating “slums”. Before and after integration, predominantly Black areas were labeled “hazardous” for lending by the FHA and HOLC, with disregard to the economic status of the residents. After D.C. became majority Black by the 1980s, the government began to decrease the amount it invested in the city. The city continued to slow the building of new homes and put public housing projects in Black neighborhoods instead (p. 10, 37, 56).

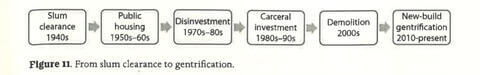

Figure 4. (p. 183)

Deterioration of public investments

During the decades of disinvestment, infrastructure, public goods, public housing, and education quality deteriorated. Rent prices for housing projects were based on income, but since low-income families were prioritized for these homes, projects generated little surplus money for upkeep and maintenance. Deepening the distress, the Nixon administration cut government spending on the public housing program by 76%. School lunch programs, food stamps, medical assistance, and job training were all defunded as well, pushing more people into poverty (p. 72). Many schools in the city could no longer hold extracurricular activities for children and some schools were closed because of the lack of adequate staffing (p. 82).

As disinvestment increased, the quality of life for many Black Washingtonians deteriorated. The job market suffered. Crack cocaine became a way for some men to make money. Unemployed and underemployed people (primarily men) were able to make money from the despair of those who had turned to drugs due to hardships. Underserved children also participated in the drug trade to alleviate boredom (from closed schools and the lack of extracurriculars offered) and financial strain on their families (p. 89). Public housing projects, occupied by vulnerable low-income families, became an ideal spot for drug use and trade (p. 72).44

Washington D.C. began building public housing primarily in Black areas in the 1940s. Blocks of homes and middle-class families were uprooted to establish public housing projects in Black areas that were deliberately downgraded by HOLC and FHA. Uprooting homeowners to establish public housing would ultimately work to keep Black people from building wealth, leaving them in poor conditions. The construction of Barry Farm Dwellings (1943) and East Capitol Dwellings (1955) invited many lower-income renters into established, largely home-owner-based Black neighborhoods. The construction of Barry Farm Dwellings sacrificed 23 homeowning Black families (p. 41). Over time, Barry Farm shifted from a community of homeowners and business owners to an area with few homeowners. East Capitol Dwellings was originally nominally intended to be an elite community housing project, but homeowners objected to its construction. East Capitol Dwellings was built despite homeowner resistance. New homes for sale were sparingly built in D.C., so the primary option for many Black residents was to rent. Public housing became home to both low-income Black migrants from the South looking for work and Black middle-class families. These majority Black-occupied dwellings deteriorated due to decades of disinvestment (p. 71).

Carceral investment

The funds that were taken from public schools and housing during the Nixon Administration were reallocated to the police department and prisons by the 1980s. Washington D.C. had the highest homicide rate in the country between 1988 and 1992. By 1997 half of Black male youth in D.C. were in the carceral web of being in jail, on bail, facing a warrant out for their arrest, or on probation. Instead of opening jobs, maintaining public housing, and funding schools that might target the root cause of drug selling, usage, and the violence that inevitably comes with poverty, the government invested in prisons and policing, which amplify negative impacts felt by underserved communities. Police were able to confiscate property from those with drug-related arrests; police confiscated cars, jewelry, and cash, homes, and buildings (p. 127, 134).

Stagnant property values

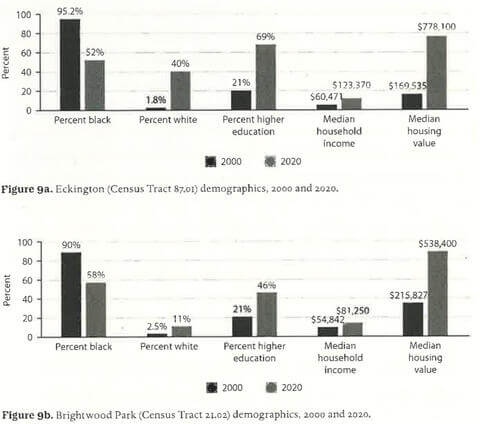

Because of disinvestment in housing and public services combined with heightened investment in the carceral system, the value of D.C. property remained flat over time. The government did little to maintain buildings, streets, and public property. Golash-Boza writes, “At the end of the twentieth century, housing prices had barely budged from their 1980 values (after taking inflation into account)” (p. 160). The relatively low property value attracted investors, who often demolished such properties and replaced them with condominiums, which were often unaffordable to long-term D.C. residents. Thus, these investors displaced long-term Black residents, who were economically pushed out of their homes and neighborhoods. The rebranding of Washington, D.C. from a devastated Black city to a new and improved real estate hotspot attracted highly educated young adults to the city. Shaw went from 90% Black in 1970 to 30% by 2010.

Figure 5. (p. 161)

Homeownership in the District shifted from Black to White. The lack of affordable housing built for long-term D.C. residents (primarily Black) contributed to a decrease in Black homeownership in the city, and an increase in non-Black homeownership. As more non-Black individuals moved to the city, more Black residents were displaced. The city sold their land, some of which contained public housing dwellings, to investors to demolish blocks and rebuild them for affluent non-Black newcomers.

Closing remarks

Golash-Boza’s research shows that homeownership has not been a guaranteed path to wealth accumulation. The alleged positive effects of homeownership on Black wealth have been exaggerated when looking at the hurdles Black Washingtonians have faced in housing. Because of “slum” clearance of middle-class Black homeowning communities, the initial uprooting of homeowning families to establish public housing dwellings worked to decrease the rate of Black homeownership. Furthermore, because of gentrification’s crucial step of disinvestment and American internalized racism, property values of homes owned by Black individuals did not increase as did more broadly. When developers and their allies in the government target Black cities for carceral investment and public disinvestment, property values remain stagnant or plummet, and wealth is not generated unless there is a significant shift in the community (p. 164). Home value in Washington, D.C. did not start to drastically increase until the 2000s, during the final stages of gentrification (p. 163 Table 4).

Intentional and targeted policies are essential to rectifying the damage that the gentrification process has done to Washington D.C.’s Black community. Some modest solutions to repair the damage done to the Black community due to deliberate displacement have been under consideration at various government levels for years with little progress on implementation or the improvement of programs already in place.

The Rental Housing Act of 1985 applies rent control to all rental units in the District of Columbia, unless those who qualify for exemption register with the Rental Accommodations Division (RAD).3 This law also protects against evictions. However, as the city demographics change, non-Black newcomers with higher incomes are disproportionally benefiting from rent control. Many long-term Black and low-income residents are not occupying these rent-controlled units, making the law less effective in protecting Black Washingtonians from gentrification.5 Designating rent-controlled units to those with lower incomes and whose families have consecutively lived in D.C. prior to 2000 may be a way to make the law more effective.

Increasing homestead property tax deductions for long-term or returning residents could promote homeownership by decreasing the financial burden of owning a home, thus Black Washingtonians may be able to keep the homes they own for generations. Holding onto their homes would allow Black homeowners to accumulate wealth from homeownership in gentrified Washington, D.C.4

Opportunity zones facilitate gentrification in many cases. Opportunity zones incentivize the investment in and establishment of new businesses in designated, lower-income areas.6 The goal is to economically improve areas, and the outcome is more gentrification in areas designated as opportunity zones. Higher-income people flock to opportunity zones and lower-income people tend to leave. Opportunity zoning designation increases the property value of new establishments, such as homes or businesses, but does not increase the value of existing ones. Favoritism also plays a role in opportunity zone designation and its lack of effectiveness in raising the quality of life in areas most in need of economic improvement. Designating areas by distress level, where areas with highest levels of distress are designated as opportunity zones first, could give more purpose to the program. Investing in current infrastructure, resources, homes, and businesses as well as new ones could decrease the negative impact of the gentrification process, by benefiting existing populations as well as newcomers.

Improving the quality of homes covered by the Home Purchase Assistance Program (HPAP) could also contribute to lowering the financial burden of maintaining a home. The program helps lower-income individuals purchase homes, but the homes they are able to afford even with help of the HPAP may not be able to help individuals build substantial wealth because of often-unaffordable home maintenance and repair expenses. Expanding the program would help more people benefit from HPAP since it is a lottery, but augmenting ongoing support for home maintenance and repairs would further amplify HPAP’s ability to overcome impediments to wealth building through homeownership.

Deliberate policy innovations to overcome the legacy of past racial discrimination in housing must be a top priority of government officials if equity is to be achieved at some point in the future.

References

1. Golash-Boza, T. (2023). Before gentrification: The creation of DC’s racial wealth gap. Oakland, CA: University of California Press.

2. Shoenfeld, S. (2019). Mapping Segregation in D.C. Washington, D.C.: D.C. Policy Center. https://www.dcpolicycenter.org/publications/mapping-segregation-fha/#:~:text=They%20came%20into%20wide%20use,ruled%20them%20unenforceable%20in%201948.

3. Department of Housing and Community Development. Rent control. https://dhcd.dc.gov/rentcontrol

4. Alfayazi, M., Amini, A., & Kurban, H. (2024). Homestead Tax Deductions and Home Values: The Case of Washington DC Versus Maryland. The Review of Black Political Economy, https://doi.org/10.1177/00346446241275200

5. Aoba-Metro.org (2023). At Issue DC - The Inequities of Rent Control. (2023).

https://www.aoba-metro.org/advocacy/at-issue-dc---the-inequities-of-rent-control

6. Kurban, H., Otabor, C., Cole-Smith, B., & Shankar Gautam, G. (2022). Gentrification and Opportunity Zones: A Study of 100 Most Populous Cities with D.C. as a Case Study. Cityscape, Vol 24, No. 1 https://coascenters.howard.edu/sites/coascenters.howard.edu/files/2023-02/Gentrification%20and%20Opportunity%20Zones%20Article.pdf